A1C Larry Sutherland Part II: The Attack on Phan Rang

| S:2 E:78

Airman First Class Larry Sutherland joined the Airforce at 17, and signed up for the Security Police training program. In Vietnam, many Air Force bases were completely surrounded by guerrilla forces, so the USAF Security Police were specially trained to protect them from direct attacks and sabotage.

During his training in North Dakota, Sutherland and some fellow soldiers wanted to “get even” with some missile security personnel that they took issue with. To do so, they broke into missile silo, but they were caught. Two members of the group went to prison, but Sutherland was found innocent of sabotage, and avoided being court martialed. Sutherland was then given a choice: Stay in North Dakota, or train at Schofield Barracks in Hawaii, and then head to Vietnam. At that time there was a rumor that 75% casualties were expected in the unit he would join in Vietnam, but Sutherland wanted to get out of North Dakota so badly that he didn’t care. So, he went to Schofield.

According to Sutherland, the Security Police training at Schofield was worse than Vietnam. He said the instructors were “the most sadistic, mean bastards I've ever seen in my life or since. I could not believe that anybody could be so mean and hateful, in all ranks, from two stripers up to the officers. They just hated us. They treated us with such contempt...And when you fell out, and guys did, because guys were dying of heart attacks, they went over and pissed on them. That's the kind of people they were. They were pissing on dying people. I saw it with my eyes. I can see it till the day I die.”

After completing his training, he was sent to Vietnam, where, due to the high casualty rate, he was sure he was going to die. He was stationed first at Pleiku Air Base, and then Phan Rang Air Base. Both bases were surrounded by guerilla forces.

One Sunday night at Phan Rang, the Viet Cong launched a surprise attack. Alcoholism was a serious issue in his unit, so many of the Security Policemen at Phan Rang Air Base were intoxicated when the attack began. A few of these intoxicated men were in a bunker with Sutherland during the attack, and no matter how much he kicked and screamed, they wouldn’t get up to fight. They just rolled over and went back to sleep.

Upon returning to the states, Sutherland was tasked with monitoring protests in New Jersey.

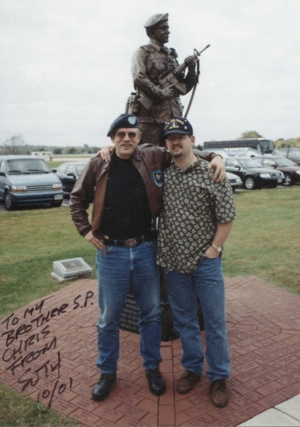

Sutherland is on the left in the picture above.

Where to Listen

Find us in your favorite podcast app.

Ken Harbaugh:

Hi, I’m Ken Harbaugh, host of Warriors In Their Own Words. If you love listening to this show as much as I love hosting it, I think you’ll really like the Medal of Honor Podcast, produced in partnership with the Medal of Honor Museum. Each episode talks about a genuine American hero, and the actions that led to their receiving our nation’s highest award for valor. They’re just a few minutes each, so if you’re looking for a show to fill time between these warriors episodes, I think you’ll love the Medal of Honor Podcast. Search for the ‘Medal of Honor Podcast’ wherever you get your shows. Thanks.

I’m Ken Harbaugh, host of Warriors In Their Own Words. In partnership with the Honor Project, we’ve brought this podcast back at a time when our nation needs these stories more than ever.

Warriors in Their Own Words is our attempt to present an unvarnished, unsanitized truth of what we have asked of those who defend this nation. Thank you for listening, and by doing so, honoring those who have served.

Today, we’ll hear from Airman First Class Larry Sutherland. After almost being court martialed, Sutherland was given a choice between staying in North Dakota, or going on a suicide mission to Vietnam. He chose the latter, first joining the other “bad boys” of the Air Force for brutal training in Hawaii, then deploying to Vietnam as a Security Policeman that was tasked with protecting bases from the surrounding guerrilla forces.

In this final part of his interview, Sutherland describes the attack on Phan Rang, and monitoring protests in New Jersey.

AC1 Larry Sutherland:

So we moved on to Phan Rang December 16th, 1968. Another, I think it was A Flight or C Flight came up and relieved us and we went back to Phan Rang. Two months of nothing but sandbags. Filling sandbags, making bunkers, make work projects, build a new latrine, repaint the barracks. I painted murals. It was just every kind of goody G-job you could think of, grunt work.

Well, it was that way all the way up to January 26th. And that's when the bottom fell out. That's when they hit the base hard. It was 12:30 at night. I was drinking with the Australians. They were stealing our poncho liners, we didn't know it at the time. I heard a siren and somebody said, "That's an ambulance". I says, "On base ambulances don't use their sirens. We're under attack". And they says, "No, we're not". And I heard whomp, whomp, whomp, they all ran out the door. I ran out the door of the hooch. I looked up on the ridge line where the rocks usually controlled that ridgeline, west of our camp, and I saw three purple flashes. I could hear the 122s whistling over my head. And as I was pointing to the rockets, I was standing in the entrance to the bunker and I became the doormat. Everybody went right over the top of me to get in the bunker. Then they told us to get out of the bunker and go collect our weapons. I went to the arms room, Captain Hockster was doing the Burt Lancaster scene from Here to Eternity. They wouldn't issue us weapons until they got a call from CSC. So Captain Hockster jumped through the window, pushed the kid out of the way, and started handing out M-16s and ammo. I had a camouflage M-16. I was the only M-16 in the unit that was camouflaged. He had my name on it. I says, "This isn't my weapon". He goes, "It doesn't matter. Get to the bunker". So I grabbed my M-16 and a Starlight Scope and some ammo, gun, and Grizzard grabbed an M-60 and some ammo, they were drunk, I was kind of drunk and we handed out to our bunkers. I was in my underwear, a flack vest and a helmet. That was it. I took the bunker, a tower in front of me opened up on movement out in the bush. Scared the hell out on me, I opened up on the movement. I tried to get the guys to wake up and join me. They could not be roused. I was there by myself. My Starlight Scope wouldn't work. I started crying. I thought I was going to die. It was real. They were on base. I had a radio. I could hear them. They were shooting the wounded. George was out there, I knew, all by himself in a tower. We were sending out V-100s to reinforce him. Barth and the rest of them were grabbing Jeeps and throwing ammo in the back. They came through the compound with a deuce and a half and said, "How many want to go to the Juliet Sector"? Well, I didn't see the deuce and a half because I was already in a bunker. Twenty guys jumped into the back of the truck and they raced out to the area. Powers is one of them, I'm sure of that. And he was one of the ones that got into the hand-to-hand combat. He brought back a bloody Ho Chi Minh sandal that he took off a guy he killed the next morning. I remember that. He's probably still got it.

We realized that night that this was the real McCoy, this wasn't just dodging rockets. This was going to be hand to hand. This was going to be everything we were trained for. Everything. That was the night you found out what you had. That was the night I prayed to God, that if he just let me live through that night, I'd be good for the rest of my life. I let him down, he didn't let me down.

But it was the absolute scariest, darkest, most pitch black night of your life. The next day when you went down and looked at who they killed, who we killed that were VC, I'd say about a third of them worked on base, the civilian contractors during the day shift. I recognized my laundry boy, one of the barbers, and a guy that used to exchange pee for MPC out at the strip where all the whorehouses were. He was one of the VC we killed. They were all moonlighting for the VC. Some of them were NVA.

In Vietnam, there's no days off. There's no Sunday off. You knew it was Sunday because the Stars and Stripes had color funnies, but that's the only way you knew it was Sunday, so every day we ran our mile and a half, we did our PCPPT every day. We were all tough. But we were also alcoholic, and nobody told us they were going to hit that night, so everybody was pretty liquored up, as per usual, when the rocket happened, so these guys got in the bunker with me. They could see I was all pinging and fired up, so they felt secure enough to go to sleep on me. They passed out, both of them.

I was angry. I was mad, because these guys normally trusted your brother and you could lay your life down and not worry. These guys had let me down while they were chemically impaired. I took it as a personal thing, and I was pretty upset and I just felt I was out there all by myself. I had no help. I couldn't get any help. There was nobody checking on me to see if I was okay. I just had to tough it out. Tough that five and a half hours out.

I was kicking them, I was screaming at them, I was crying. They told me, "Fuck you. Leave me alone." They just roll over and went back to sleep. I guess they felt if they were going to die, they'd rather die asleep than awake. They could care less. It was no big deal to them.

If I'd have been just a regular security policeman, I'd have probably run for my life. That's not taking anything away from security policeman. That's just the way Larry was. But Schofield gave me courage enough to stand my post and man my post and not run. That's what I learned at Schofield and that's what I learned from these guys is the worst thing you could do is show fear and cowardice. I was crying and I was upset but those guys were passed out, so I didn't care if they ... I could show it, I could let it all out, because it was just me and the VC at that point. I also knew if I screamed and cried and did all that, I'd get my heart pumping. This is things we learned in safe side that to scream, get your heart pumping, and get you that adrenaline going, and I did it and it worked. But all my screaming was at these guys to wake up.

Jim, they knew exactly what was coming and I can show it to you and prove. Colonel Fox's book shows a letter dated January 10th, 1969 saying, "Prepare for these bases to be hit. Intel shows weapons caches are increasing around these areas." They had found some instructions where they had bases laid out in areas that were weak. They collected this evidence. It said that we were going to be hit and one of the [inaudible] said, "Send this to the 82nd Wing in Phan Rang, and let them know that this is coming." None of us were warned. None of us were even told that this was coming. It was totally out of the blue, because if they had told us, we would have been prepped and ready. I'm sure of it. It was almost like a Pearl Harbor thing, like they wanted it to happen, they knew it was going to happen and they allowed it to happen, but it was the scariest night. It was brutal. They were blowing up F-100s on the flight line, they were tossing satchel charges into the intakes, they got past the dog handlers ... When the canine finally alerted on them, one canine got a grenade in the mouth, saved his handler's life and died. After action reports show that the enemy had been probing us for two months, and that they knew all the weak points on that base but they didn't know about the 822nd in the area that they went through.

To be fair, there was some local base security police that was in that area too. It wasn't totally safe side, but a majority of us in that area that secured it were 82nd combat security policemen.

And This was the ranch hand area where they kept all of the Agent Orange airplanes and Pat Nugent, the son-in-law of President Johnson, lived and worked in that area while we were defending it. I know that two died and they were as a result of accidents. Other than that, we had no casualties.

I jumped on a bus and went down to look at the KIAs they were bringing in in body bags. They laid out 18 bodies. They looked like roadkill. Some of them had been hit with 50 calibers. Henson hit one guy carrying satchel charges, blew up, and killed the guys on either side of him, but the guys down in the bunkers, I didn't hear too much, because they were another flight. Frank Powers and them were another flight but actually they jumped on the deuce and have to go out there and reinforce that area, but they got into it. They got down and got funky. They really got into it. Everything they had been trained came to the surface, and it was like automatic. It was just clockwork. They did it and they did it right. George Weimer did it right.

We used to call George Willy the Worm Weimer. He was just this little monkey guy, a little skinny runt guy, that everybody made fun of. He looked like Ernie on My Three Sons. But whenever you would see him do something superhuman, it just made you want to try that much harder. I couldn't do the overhand, hand to hand ... I mean, monkey bar thing but he could and he could do it well. He turned out to be ... That little pint-sized guy turned out to be the biggest hero of them all, that I knew, and when he was getting that medal pinned on him in North Carolina later, I was going, "Why isn't he getting a Bronze Star? Why is it just the commendation?" I mean, he was out there all by himself with nobody and he could see a lot going on but he didn't have anybody like I did in the bunker to make him feel like he had somebody. He was by himself. With that M60, just cooking it off. You know? They brought him more ammo out but for a while there, he was surrounded. He never cried about it. He never made a big deal about it. He just toughed it out. Toughed it out. Good old George.

What happened- they came in and started policing up the wounded ... Vietnamese were coming in on motorcycles, picking up the wounded VC and driving off with them. You couldn't shoot them when the sun came up. Mac V rules of engagement forbade it. When the sun was up, you needed permission from them to shoot. They knew that. The VC knew that, and they went out and policed up some of their wounded and took them off on motorcycles and we couldn't do anything about it. That's a true story.

These were just mutt dogs that hung around the camp. You needed a pet, somebody wanted a pet. So these mongrel dogs, they don't look like anything like dogs in the States. They had corkscrew tails. We're looking genetic strains of dogs, I guess they fatten them up for food over there, but we took them as pets. But everybody adopted Buster, and the other one was Colonel.

The 1041st had K9, and I have photographic proof of that with their Blue Berets. They did have K9. However, they realized once they looked into it that the K9 troops in Nam, they had it handled. They knew what they were doing, they were pretty good. There wasn't any way you could make it much better than the way they did it. But as far as all the rest, they needed some backup.

The K9 was very valuable. We would've suffered a lot more if K9 hadn't been there. I can tell you a couple of nights I called in K9 and they alerted, and the base went on augment-T status, where they roll everybody out of bed and the cooks and the clerks get a gun. The one night that I pulled Juliet Sector, I heard noise. Two weeks before the ground attack I heard laughter coming from the canal. I called the dog handler, he alerted. They called in a quick reaction team. They came out and they said, "What do you got?" And I says, "The dog's alerting. I'm hearing noises." They listened, they heard it too. So they declared an alert, they rolled everybody out of bed. Lieutenant Miller came out, he wanted to know what the hell I was doing in Juliet Sector when I was supposed to be on sandbag detail. Well, I for $20 pulled a guy's post. $20 was a lot of money. This guy was in a rolling card game, winning big, held up $20, says he'll take my shift. I grabbed it out of his hand. I went and did the Juliet Sector and I could hear them. That was two weeks prior to the attack. What does the post intelligence tell you? They've been probing us for two months. We had VC on base that night and I did my job. I heard them, I alerted. I did everything I was supposed to do, and Lieutenant Miller said I'd never pull that post again and blamed me for causing the base to go on alert. He said, "I should have known it was you, Sutherland." And he never came up and apologized to me later and said, "Well, thank you." And hey, you did your job right. Nobody ever acknowledged that. But I heard it. I heard them when they were coming through there that night, prepping and learning escape routes and all that.

It didn't take long for every base that got a safe side troop up there to find out they were all brainwashed, and they were all pretty much into their own thing. They enjoyed their status and the fact that they were ostracized. They seemed to have enjoyed that. When we got there, we had to stay there seven months instead of four months and you better learn how to make friends with these people you're going to be working with or you're going to get the cold showers, you're going to get all the harsh treatment, that not everybody else gets. They can find ways ... The regular base can find ways to make your life miserable, if they don't like you. We tried hard. We had to mend fences and, basically, we did it by scrounging, borrowing, stealing, and trading. We were real good at scrounging and trading. You know? We could get you a Jeep, we could get you a tank. We could probably get you everything but a helicopter and airplane. If you wanted it, we could get it for you. Stealthily.

You had the biggest Jeep thief in here yesterday with Bob Kadu. He'd go down to the parking lot in front of the BX and he'd pick out the nicest Jeeps and drive them off and repaint them. I don't think we had two Jeeps that were really issued to him. All the rest were stolen. Well, first thing he'd do is get out a rattle can of OD paint and cover the real number and then get it over to our area and he went in and asked Sergeant Taylor, "What's your favorite number?" He told him and he says, "Okay, that's your Jeep number." Sprayed it on the hood.

TDY, temporary duty assignment, anything under 179 days. If you pull 180 days, you got a PCS tour credit. The problem was at that time is you couldn't send a person back to Vietnam but once every four years, on a PCS tour, but you could TDY them in and out of that country to your heart's content. They even had a list of how many of us had been past the magic mark that they couldn't rotate back, but they figured out a way. They sent Dulles and Steinke back. They sent them back early and they had to do Phan Rang all over again. Some of us guys got Phan Rang twice after coming back.

The night before we were trying to leave, we came under attack again. Bob Kadu and I go, "Oh no. Here it goes again." We went outside ... We heard the impacting of the mortars on base at Phan Rang and we looked up and our freedom bird was making a U-turn heading back to Clark. I was sure this was the day I was going to die, because I was so close but I was going to be one of those stories that didn't make it out. When that freedom bird backdoor, the pod doors opened, pedal doors opened, and I got onto that C-141, I didn't cheer until I sat down in that seat and buckled the seatbelt, and somewhere I have a photograph of that freedom bird, because I never thought I was going to go home alive. That was the reality of it was getting in and buckling that seatbelt. I knew then I had made it, I had survived the war. I have a photograph that shows most of us that you've interviewed in the barracks, the hooch there before all that happened, everybody's duffel bags are being packed, and you can look at that picture and that was the best we ever were. We were never tighter. We were never stronger. We were never physically more fit than that last day in country, and when you look at the photo and you see the expressions on their faces, it's that look of relief. You know? The FIGMO calendar is filled. You can go home now. It was electric. It was like everybody's 100th birthday parties rolled into one. You look at the expression on everybody's face in that picture and I say that was the best, the best day, the best we ever were. We had done it. We filled it. We did our job well, and we passed. Not only did we survive Schofield, we survived Vietnam and made it home, on our way home.

I wouldn't be here today if it wasn't for B flight heavy weapons section and the people in it, and that these men ... I love a lot of people, I have family, these people are more important to me than anything on the face of this earth. That's why I've spent four years trying to track them down and bring them all back together again. You see it when you put us all together. It's still there. We pick right back up where we left off like everything happened yesterday. These guys and the nicknames come to the surface. I was never on a football team, I was never on a baseball team, I was never picked for basketball. My team was B Flight, heavy weapons section, and they picked me, I played with them, and it was wonderful. We won, we came home. We had a winning season. And that to me, the fact that they accepted me into that brotherhood, is the most valuable thing I have. And the fact that a runt, punk kid from Bakersfield, California could end up with these heroes and be considered one of them, I'll take that to my grave. These men were supermen. They were fantastic human beings. It was just the right mix. Somehow it all came together and it was beautiful. I hated it then, I swore every day. But I went back into the reserves trying to find people like that again. I never found guys like that in my life again, that cared for you as much, would do anything for you. Even if they hated your guts, they'd fight for you. And it's like when the stuff hit the fan, it was back to back and they were there with you, and it was just automatic. How does it happen? I don't know. It was just the right mix. I can't tell you that every Safeside unit was that way, but I can tell you B-flight Heavy Weapons Section was the best unit I have ever been in my life, and I've been in probably 12 different military organizations.

When we were rotated back to the States, they put us up in Seymour Johnson Air Force Base. That was our home base for the eight 22nd. We started the school back up there. We got in the new people, the FNGs started transferring in to take the place of people like McNamara and Powers that had done their tour and got out. So we had to build it up and the punk kid from Bakersfield became an old timer. I was a battle hardened vet and all of these young kids from California were looking up to me, I felt like I was special. But I still had only two stripes and I was 19 years old. But here I had these kids thinking I was some kind of whoa dude, and we stayed there. We were on one-hour alert notice all the time that we were supposed to be able to make it to the flight line with your bags packed and deploy anywhere in the world within an hour.

Well, we got kind of loose about it. Some people took off on the weekends. One morning on a Saturday morning, they gave us the one-hour notice and we were thinking, "Oh no, guys are off base. Guys are up in New Jersey visiting family." Well we go down and we grabbed our bags out of the mobility box and here's all these dirty Vietnam fatigues that we'd never laundered since we've been back. All of our war gear was in this one building. We put on our stuff just like we're going back to Nam, but this time it's New Jersey. It's not Pleiku, it's McGuire Air Force Base. So we pull in there and they're sandbagging up the main gate and it's looking like Pleiku. And I'm thinking, "This is America. What the hell is going on here?" So finally ... and I was at the point where I hated the Air Force and I wanted out in a bad way. I was talking in the barracks, making it loudly be known that I might just jump the fence and go and help the hippies take Fort Dix, because they were breaking on to Fort Dix to free political prisoners, or draft dodgers that were in a prison there. And the Army was doing a pretty good job of holding them at bay, but McGuire was part of Fort Dix, so they were worried for Fort McGuire and we were supposed to bolster that. We got there, I was making noise. Bless his heart, Sergeant Bill Fetsko took me outside and said, "Sutherland, cool it. Sergeant Porter's writing down everything you're saying. You don't want this on your record, just cool it. Keep your mouth shut. Do what you're told. Pretend like this is Vietnam."

And he's here today, Bill Fetsko, and that's the one thing I remember about the old timer because he was the oldest Buck Sergeant we had. He came in after college, but he was like a big brother that watched out for the kids. And he thought enough of me, his brother, to go back for a man, never leave a buddy behind, to take me outside and true my compass and say, "They're going to get you if you keep talking."

So I just gutted it out the next day, put on my cammies, did the old right control drill formation that they drummed into us that we could do by heart, and we put the brave face on and nobody got on McGuire. But the guys that were all AWOL, they were within miles there, but we couldn't call them and say, "Just come over," because their mobility gear was back at Seymour Johnson. So they all got Article 15s and court marshals when they got back because they weren't there to deploy. But a lot of people ... I talked to a guy the other day that was part of that, that didn't make the deployment to McGuire. Yeah. He was in New Jersey visiting his folks and he broke down crying talking about it, because they put so much punishment on him for missing that, that to this day he hates the Air Force. He hates the people and the higher ups in the eight 22nd that humiliated him like that and made him sign out for chow and confined him to barracks. But, he missed the boat. He wasn't there for when the feces hit the fan, and that's bad when you're not there. Like those two guys that wouldn't help me in the bunker that night. Once you let a guy down once, you remember that the rest of your life. And I can say, Lieutenant Karbowski, now Colonel Karbowski's crew, that was the best of the best. We were the Beatles. We were the best. Nobody was better than us. He was Frank Sinatra there, nobody could do it like we could do it. And if you saw it happen, it was just like instinctive. Everything fell into place. You didn't have to bark commands. When the bullet started flying, everybody assumed the position. Put it on A for awful.

Because when I told you the last picture was taken, that was our best and tightest day. Something happened when we came back to the States, it fragmented, it fell apart. It was like alphabet soup, it just went in all directions. Guys were looking for girlfriends, guys were trying to get home, and all that tight bond and everything that happened it was just gone. I felt that the Black guys you palled around with, they wouldn't have anything to do with you Stateside. It changed. All of a sudden it was, "What happened to that thing we had back then?" But I will tell you this, that everybody that I'm talking about was 19, 20, 21, hormones raging, wanting to start a family. They didn't have time for this crap we were going through 24 hours a day at Seymour Johnson. You were trying to find any way you could to get out of it, to get away from it, to distance yourself from it.

If you see the movie Deliverance, that scene in the end where Ned Beatty tells John Voight, "Maybe we not ought to see each other for a while." It's because you guys were victims of the same crime and to see your buddies there reminds you of it. And I think that's why I had so much trouble at first getting guys to come to the reunion, is they just ... To some folks it was an adventure, to others it was a train wreck. But I think once they finally put it all in place and sort it all out, they're glad to be back with their brothers. They love to be back. Every guy that comes digs it.

They were all spit and polished, starched fatigues. Our cammies and our uniforms were stuffed in these mobility bags. They still had dirt and mud from Vietnam on them. We prided ourselves in looking sharp. That day we didn't look sharp, we looked like we just came off patrol. So I put the fear of God ... I think when the hippies saw coming down, they realized they were getting the real deal. I don't know that I would've shot one of them, but there was a lot of guys in my unit that were just itching to take a few of them out. I mean, they really wanted it bad. Because here we went off and did all this stuff for our country, and we come back and we get spit on, and here's these people. And then I'm kind of sitting there and thinking, "Well, hey, maybe they're right and we're wrong." I don't know. They're getting laid more than I am. Because at that point in your life your value system was cars and women and rock and roll, and that was it. That was all you cared about at the time. And I wasn't getting much of that in the Air Force. I had no car, I had no girlfriend, and all these guys that were assaulting the base did. They had their VW buses and their girlfriends. And I thought, "Well, maybe that's what I should be doing." I don't know. Like I said, we came back home. We thought we were going to get the welcome home you see on TV from World War II. Our families did that for us, nobody else did. It wasn't until recently that they started buying us beers and thanking us.

And I always felt like I was some sort of German soldier that was in France in World War II, there because he had to be, not because he wanted to be. I kind of identified with that. But you know what? We didn't round people up and kill them, and I never shot a baby. I never saw any of my friends here do anything that would've harmed any civilians or anything like that, except for McNamara killing the water buffalo, which we knew impacted some family.

McNamara saw movement one night. Looked through the Starlight scope at Pleiku and he saw the water buffalo out grazing around a shot down C-47. So he says, "I've got movement." And they said, "Open up." He chopped that water buffalo up with a 50 cal, and it got around and we had to pay the family for the water buffalo. He knew what he was doing, so we call him the buffalo killer, or buffalo hunter. But it is not edible meat when a 50 hits it. He was that way. He just loved it. He loved the action. He loved it. The harder it got, the better he liked it. He ran a dog to death one day, just doing his five-mile run. The dog died of a heart attack. Him and Kadu. We buried Buster in a nice grave and put a headstone up. That dog died of a heart attack running with McNamara and Kadu. They were animals. They were more animals than the dog was.

Karbowwski was a good man. He had all of our respect. He never shamed us in public, he always praised us in public. And if he chewed you out, he chewed you out in private so he wouldn't embarrass you. He was a ramp rat. He was a two striper when he went off to bootstrap into a lieutenant slot. He had our respect because he never sent us anywhere he wouldn't go. That man was always there. He wasn't hiding in CSC when that hit the fan. He would come out and bring us sandwiches. Sergeants wouldn't do that. He would make sure that you were doing okay. He'd also inquire into your mental health. He could talk to you and figure out where your head was at, and whether you needed to be pulled out of a bunker and sent in for a little rest or something. He knew our weaknesses and he knew our strengths and he worked on those strengths.

We didn't get jump wings, we didn't get badges. We were supposed to get the beret when we graduated, but they held that back from us as well. They didn't care about us, the higher ups. They thought we were nothing more than just a little bit better trained security police. So we all went out and bought them on our own and we all went out in downtown Pleiku and had the patches made to sew on them. And it was the most important thing about you was that Blue Beret. And when we all went home, as soon as we were out of eye shot of the officers and the NCOs, we all screwed on our berets with our 1505s and went into the airports, bloused our combat boots and we looked pretty whoa. Went home wearing our berets, every man.

I don’t know how to tell you. It's like an American flag. Just one notch below an American flag to me. My beret means that much to me. And every man that worked hard for it, it was his diploma. It's his sheep skin, that beret. And when we see people wearing it now, we wonder if they went through what we went through to get theirs, or they just got in the career field and had one issued to us. But with us, it was like earning a Ranger Tab in the army to get that beret. And we were the first ones.

My brothers, I will do anything for. I would go to prison for my brothers. That's the kind of bond it is. I would do things I wouldn't normally do for anybody else. I can tell you this, I will not strip down naked in front of my brother that I live with. However, when I'm around these guys and they strip down to go to the showers or something like happened in the reunion in '99, it didn't even phase me. I was used to it. It was like they broke all that down. That was gone. Your brothers know your scars, know your weaknesses, know your faults, and they love you anyway. And there was that there. We didn't call it love back then, but I'm looking at it now. Man, we loved each other, and I love those guys today. I light up like a Christmas tree when I see Nemar and Kadu and Ryan and Weimer and Johnny Koch and all the rest of these brave men. And they were tigers. These guys were hard as hell, and they started out little kids. In four months they turned us into men. And I can show you before and after pictures, we looked like Timmy going in, you looked like John Wayne coming out. And every man was a tiger. Our phrase was, "Join to fight." We weren't drafted, we joined to fight. We wanted it, and every man that was there volunteered. We were all volunteers. Nobody was sent because they didn't want to go. And that's what I think about my brothers is that by God, if it's going to get hot, put us on it, we'll put it out. And we still could today. I know that.

Every problem, horrible thing that's happened to me since I couldn't have got through it without my ranger training, which told me it isn't going to last forever, just gut it out. Put one foot in front of the other, get up the pass, Coley-Coley pass. It isn't going to be forever and you're going to feel better when it's done because you did it. You didn't crap out, you didn't stay behind. You went with your buddies, you never left a man behind. We never left a man behind, and that's why today I'm going back for my buddies, because I'm not going to leave my brothers behind. And when I find them, it's electric. It's great.

Ken Harbaugh:

That was AC1 Larry Sutherland.

Thanks for listening to Warriors In Their Own Words. If you have any feedback, please email the team at [email protected]. We’re always looking to improve the show.

For updates and more, follow us on twitter @Team_Harbaugh.

And if you enjoyed this episode, don’t forget to rate and review.

Warriors In Their Own Words is a production of Evergreen Podcasts, in partnership with The Honor Project.

Our producer is Declan Rohrs. Brigid Coyne is our production director, and Sean Rule-Hoffman is our Audio Engineer.

Special thanks to Evergreen executive producers, Joan Andrews, Michael DeAloia, and David Moss.